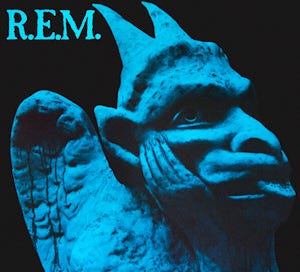

R.E.M., Chronic Town, and the Uncanny Weirdness of Small Town Living

Growing up in the 80s and early 90s in a small town 100 miles from the nearest city meant a kind of cultural isolation that would be shocking even to young people living in those same small towns today. Finding music that did not fit into the corporate monoculture of the 80s in a pre-internet world took a lot of work. Local radio would not help you, and until “Smells Like Teen Spirit” crashed the gates in late ‘91, MTV served up a big Aqua Net-ed plate of hair metal.

Around age 11 I started listening to more music on my own, but it was all 60s rock like The Monkees, CCR, Beatles, etc or rap music without explicit lyrics stickers (they actually carded you at the local Musicland to make sure you were 18!) I just flat-out did not listen to contemporary rock music.

In a kind of miracle, R.E.M. broke through rock radio and MTV’s allergy to anything outside of the mainstream. I remember hearing “The One I Love” on the local station and feeling like it cut through to my soul. Two years later, in 1989, I enjoyed hearing the far more joyful “Stand” over the airwaves. Two years after that, in 1991, “Losing My Religion” hit MTV heavy rotation and I plopped down $14 in lawn mowing money on the barrelhead and came home with Out of Time on CD. I loved it so much I went out and bought their entire back catalog on cassette (to save money) by the time Automatic for the People came out the next year.

There was one hole in my collection: their debut 1982 EP Chronic Town. I finally heard it in the most improbable way. I spent my high school summers doing corn detasseling, a menial yet essential bit of agricultural labor that’s a rite of passage among kids in rural Nebraska. Our crew, like most, was headed up by teachers making some extra summer dough. One of those teachers, Mr Christie, was a favorite of the boys. He was funny, energetic, young, and gave us a lot of encouragement on long days spent walking miles of cornfield under the blazing summer sun. One day I found out that he was a fellow R.E.M. head, and that he had even seen them in the early 80s at a live show in Omaha. He had the Holy Grail I had been waiting for too, a cassette of Chronic Town.

I listened to music on my Walkman all day while walking the rows of corn, and the day he lent me the tape I must have listened to it five times in a row. I was struck by how much R.E.M. sounded like a little punky band; by 1983’s Murmur they had morphed into something smoother and more refined.

I had caught glimpses of this early version of the band in an hour-long “Rockumentary” episode MTV put out in the early 90s which I had managed to tape off of TV and watch a million times. In another part of it I was struck by an old interview clip with Peter Buck where he praised their Athens, Georgia, homebase as a place where people could just do their own thing. Living in a small town I loved this offhand comment because it felt like one of my heroes was confirming that you could make great art while living far away from where the action supposedly was. It certainly gave me hope.

From the title on down, Chronic Town might be the most “small town” of R.E.M.’s records. Small-town life is strange because limited horizons combine with a slower pace of life, allowing more time for contemplation. For someone who isn’t totally comfortable in this world it means day after day of living inside of your head, yearning for contact with an outside world that’s also completely foreign to you. This alchemy of longing and frustration might not be fun to live through, but it sparks a unique brand of creativity.

Their small-town origins help explain why R.E.M. didn’t sound like anyone else out there. They had an obvious punk/new wave influence, but they weren’t playing post-punk. Their guitars hummed with a jingle-jangle that would make Roger McGuinn jealous, but the songs remained obtuse. At this stage Michael Stipe mumbled and blurred his lyrics, creating impressions like a modern artist instead of painting a literal picture. In fact, he never got mumblier than songs like “Gardening at Night” and “Wolves, Lower.” The clarity of “Losing My Religion” was a long way off.

As I tried to make sense of the murk, there was no doubt that songs like “Carnival of Sorts “Boxcars)” spoke to the everyday ennui of small-town life, that feeling of being trapped inside of a bubble. I lived in a railroad town where the constant rumbling of trains through the town was a reminder of my hometown’s status as a place to be passed through. After I graduated high school, they rerouted the tracks to the outside of town, so we weren’t even a bump in the road anymore.

The summer I borrowed Mr Christie’s tape came right before my senior year of high school, when my dreams of getting out of my hometown finally felt close to reality. It would be my last summer walking the rows of corn, my last summer returning to school with the peers I had failed to mesh with for twelve long years. It was appropriate then that Chronic Town ends with “Stumble,” a song about the difficult first steps of adulthood after leaving childhood behind. Or at least that’s my reading of the jangly mumbles.

It’s been forty years now since R.E.M. made their own first recorded steps. My listening habits change pretty frequently, but I keep going back to early R.E.M., and I suspect that I will until the day I die. This music illuminated my lonely small-town teenagedom and made the small horizons of my daily life feel limitless. As bad as things can get, I know I will always at least have my imagination. A band of small-town dreamers helped me unlock it like nothing else.