The current state of the country and the world is so dire that I will need some time before I can write something new about it. Considering the ways that blogs and social media are being weaponized against any kind dissent right now I am also being a bit of a coward.

Lucky for me, I found some distraction from the hellscape this weekend by going to the Outlaw Music Festival. This was my slightly delayed 50th birthday present, and for the august occasion we sprang for the good tickets. While I loved finally seeing Willie Nelson live, enjoyed seeing one of my fave current artists (Waxahatchee), was blown away by Sheryl Crow’s swagger and appreciated being introduced to the music of the opener (Madeline Edwards), I was there for one reason and one reason only: Bob Dylan.

My desire to see Dylan for my 50th was strong, stronger that the usual “I wanna see that show” interest. I didn’t realize where that feeling came from until after the concert. I suddenly remembered that the media coverage around Bob Dylan’s 50th birthday and his corresponding 30th anniversary as a performer tribute concert was the moment of my first true engagement with Dylan. I was now finally at the moment in my life corresponding with Dylan’s when I first got hip to him. It felt as is something had come full circle for me.

It was weirdly surreal to become a Bob Dylan fan in 1991. He had reached the point in his career where he had lost any sense of relevance or connection to the current pop culture. He had put out some albums in the 80s using the au courrant production methods, but they made no commercial impact, and a few of them are in competition for what’s considered the low point in his career. My vote might be for Under The Red Sky, the album he put out in 1990. It was his most recent new product on the shelves of the local Musicland. I gazed on it the year it came out, and could not believe this was the guy the cool kid two years ahead of me in school had been raving about. The album just looked inconsequential. (Dylan’s worst albums are less “bad” than they are “inessential.”)

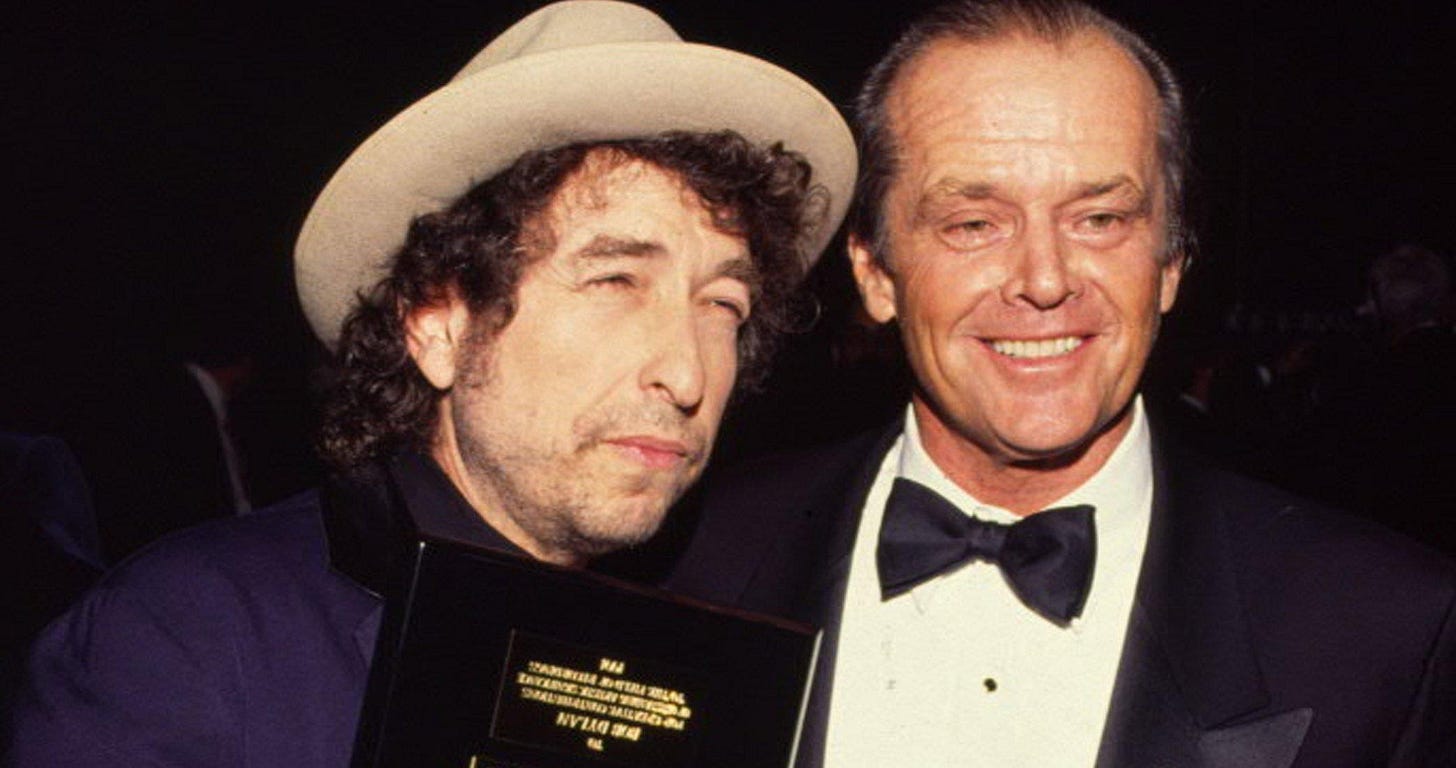

What activated my interest in this over-the-hill figure was a Rolling Stone article marking the Bobfather’s 50th birthday, and his (in)famous performance at the Grammys that year after getting a lifetime achievement award. Such honors imply an artist is well past their fertile period and well into the winter of their years. Dylan subverted that expectation by giving a strange, punky rendition of “Masters of War,” one of his most angry political songs. He performed it during the time of the Gulf War, when criticism or even reflection about it was practically outlawed.

Dylan’s voice was a impenetrable foghorn, sounding just like the hackiest standup comic Dylan parody. When he came to the stage to speak he slurred his words, which spelled out a cryptic statement:

“Well, my daddy, he didn't leave me much, you know he was a very simple man, but what he did tell me was this, he did say, son, he said, he say, you know it's possible to become so defiled in this world that your own father and mother will abandon you and if that happens, God will always believe in your ability to mend your ways.”

I saw it live, and amidst the usual awards show bullshit Dylan’s appearance stood out as something actually interesting, even if it bewildered me. Later in the year I was talking to my team’s assistant debate coach, a local college student, who told me that Dylan didn’t just seem drunk that night, he was stoned. I didn’t know what it felt like to be either, which just added to confusion.

So what did I do? I did what all young people were told back then when curious, I consulted my local library. Before I really knew Dylan’s music that well I knew him in books. (This might explain why I am now writing scholarship about Dylan rather than just listening to him all these years later.) Clinton Heylin’s Dylan Behind The Shades had just hit the shelves. I thought the cover looked cool, so I checked it out. I was immediately intrigued when I discovered that Dylan, like me, had grown up in a small town in the Midwest. I learned about the Village folk scene, going electric, the motorcycle accident, his divorce, becoming a Christian, and all the rest before I had heard more than a handful of his songs.

Suddenly this weirdo on TV, the one guy I couldn’t recognize back in 1985 in “We Are the World,” was absolutely fascinating to me. The problem was that the book taught me so much of the history that I didn’t know where to begin with the music. At that moment I had one of my biggest strokes of luck as a buyer of physical media, one so fortuitous that it could make me believe in fate. Right in the middle of my Dylan fascination, a record store in another town was going out of business and I happened to be around. I noticed the recently released Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 on cassette just sitting there. Tapes were cheaper than CDs and marked down even more, to 2/3s off. I ended up getting the box set for just ten bucks.

My journey into Dylan had been strange enough due to beginning on the page, I made it a lot weirder by doing a full-career deep dive into his music but only the outtakes and rarities. At the time it made sense since the Bootleg Series had been well-reviewed, far more than his last studio album. On top of that, his reception of a lifetime achievement reward implied this was someone whose whole lifetime of work ought to be considered at once. Initially I gravitated to the first volume, which was all Dylan in his folky mode, by far the most accessible version of him based on my tastes at the time. Soon, however, I started getting pulled to the snippets from The Basement Tapes and the Blood on the Tracks outtakes from the famous Minnesota sessions.

Despite my love of this music I did not go out and buy any other Dylan albums, apart from compilations, for years. I didn’t even seek out the classic 60s records. I was practically hoovering up tapes and CDs back then but I didn’t even give a thought to picking up As Good As I’ve Been to You or World Gone Wrong. The strange backroads and byways of his career on the Bootleg Series were so good and spoke to me so well that I didn’t feel the need to drive over to the main road. From the time I saw Dylan honk out his frenetic “Masters of War” at the Grammys I had accepted that this was not a person who could be approached directly. Nowadays as a wannabe Dylan scholar, that’s something I always try to remind myself of.

I was further reminded of it when I saw Dylan on Saturday. As is his wont nowadays, he took the stage in darkness, hid behind his piano, and used glaring lights to mess up any fan photography. In the age of constant image posting online he still insists on his inscrutability. Likewise, his performance leaned on some very deep cuts, and when he played the more popular songs, he rearranged them so radically that it was hard to find traces of the originals. A lot of people in the audience complained; I laughed. Once again, like back at the 1991 Grammys, the old trickster refused to conform to expectations or to reveal himself to us. It’s why this fifty year old still carries the same fascination sparked 34 years ago.

one of your best, and perfectly timed; dylan's history and continuous rediscovery seems to exist outside the dangerous pettiness of the times we find ourselves in. his appearance on stage these days comes to us as some ancient monk, here to deliver the same message in different clothes. that message - whatever each of us takes from it - somehow both transcends and mocks what is swirling around us. better late than never, sir! thank you for this piece (peace).

https://open.substack.com/pub/johnnogowski/p/bobs-finale-on-second-thought?r=7pf7u&utm_medium=ios